"A widow with seven children, Malke married a fine young scholar from the yeshivah whom the saintly Rabbi Yossef Zundl Hutner and his flamboyant wife had found for her. Malke had been supporting her family on the income from her store, which ... had its biggest earnings on market day. On the first market day after their wedding, Malke’s husband left the beth midrash to assist his wife for a few hours at the store. It was the first time in his life he had ever faced a real scale, and though he knew all the halakhic and ethical regulations pertaining to scales, he did not in fact know how to use one, as his wife discovered when she gave him a kilogram of salt and he carefully placed both the salt and the weights on one side of the scale.

"Malke was outraged. In an unprecedented move, she closed the store at the height of market day, grabbed her husband by the sleeve, and marched him through the market square to the home of Reb Zundl. When she arrived at the rabbi’s house, she said, 'Rebbe, you gave him to me, you take him back. I am a hardworking widow who is trying to provide for her orphans so that they will grow up to be proper human beings. I do not have the time to raise yet another child.'"

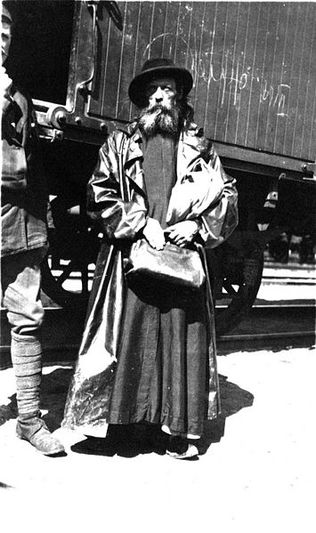

That patience would have been required to deal with more than just a groom's impracticality. There were all kinds of reasons to be unhappy with a match. For example, after my great-grandmother Kayla, who I've already mentioned in connection with a priest, married my great-grandfather Schlomo Zalman, she ran right back home. Why? Because he was more than twenty years older than she was, and even had children about her age. (But don't worry. She went back to him after a while.)

There were plenty of reasons to be unhappy with a match. But divorce, while far from uncommon, was obviously something to be avoided if possible. The best thing, it would seem, would be to break off the engagement before the wedding-day arrived.

In fact, though, breaking an engagement wasn't considered any great shakes either (unlike breaking a bunch of crockery, which is how an engagement was sealed at the time.) Possible consequences and deterrents included:

Rashi

Rashi Threats to be force-recruited into the army, in the case of grooms protesting matches their parents had arranged. One groom faced with this threat tried to get around it by sending an anonymous letter to the bride's parents: "No good will come of this marriage!" he wrote. But to no avail. (Cited in ChaeRan Freeze's Jewish Marriage and Divorce in Imperial Russia.)

There was the prospect of getting taken to court by your parents, if you defied their wishes in marriage. Which, believe it or not, really happened sometimes. One case cited by Freeze resulted in a sentence of 3-6 months in jail for the errant bridegroom, followed by exile. (This particular threat pretty much fizzled out in 1861, when some Russian judicial reforms were made.)

| And last but not least, a dybbuk might enter "the body of a person because of a sin they committed, especially breaking a vow or canceling an engagement." (Ethnographer Shmuel Shrayer, quoted by Deutsch.) However … never underestimate the determination and ingenuity of the young. Here are some of the ways they still found to wiggle out of engagements: Running away to a yeshiva or state rabbinical school (for wouldn't-be grooms) |

Running away to a "special school" (for young women.) These might include "schools for midwives in Mogilev" and "schools of dentistry in Kharkov," according to Freeze.

Joining one of the latest political movements, "like nihilism, populism, or socialism: these close-knit conspiratorial circles functioned as ersatz families and helped single women contract the fictitious marriages that conferred internal passports and the right to reside outside the parental home." (Freeze)

The ever-popular Converting to Christianity. Rachel Elior notes, in Dybbuks and Jewish Women, that "between the years 1737 and 1820 more than two thousand Jewish women converted to Christianity in Lithuania ... From folktales and dybbuk stories we know that this phenomenon was connected at least partially to the fact that apostasy was perceived as a refuge from coerced sexual relations and arranged marriages."

Conversion had a bonus feature, too: it made the authorities more inclined to help you get your parents off your back.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed