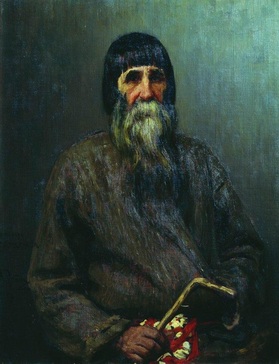

A Shy Peasant, by Ilya Repin

A Shy Peasant, by Ilya Repin It's not the easiest question to answer quickly … unless you're Professor Jeffrey Shandler of Rutgers University, who just published a book called Shtetl: A Vernacular Intellectual History. Earlier this week, Tablet Magazine put up a fantastic podcast interview with Shandler, and it takes the professor only a few short minutes to iron out most of this issue's many wrinkles. I don't want to misrepresent what Shandler says, because he actually allows for various definitions (and you should listen to the whole podcast), but here's the heart of the matter:

"… what might be thought of as an archetypal shtetl is a community that’s centered around a marketplace ... peasants from surrounding farm communities would bring whatever they had raised … and sell it to both people who lived in the town, and then to brokers who would buy all this produce and ship it off to various locations actually all over Europe … and at least originally, the core activity of Jews in these towns was that they were there to facilitate this economy … either overseeing production ... or they were the brokers who were buying and selling and moving things, or they ran stores that lined the marketplace that sold to the peasant farmers the things that they needed that they couldn't make for themselves."

Two Ukrainian Peasants, by Repin

Two Ukrainian Peasants, by Repin There's no doubt that Shandler is right: this is a big misperception. Take our attitudes about Fiddler On The Roof. We might all generally know, yeah, it's Broadway, it's not history … but maybe we've also thought: but shtetls were sort of like that, right? Close-knit Jewish communities rooted in piety and … um, tradition … where, when Gentiles did appear, they were associated strictly with calamities (or perceived calamities) like intermarriage, eviction, pogroms?

Well ... if we thought that, then we thought wrong. Because if the marketplace involves a lot of interacting between Jews and Gentiles, then Gentiles must be something other than just outsiders and bringers of calamities in the lives of Jews. True?

True.

Ukrainian Peasant, by Repin

Ukrainian Peasant, by Repin An interesting wrinkle:

"… until World War I the market was largely in the hands of the grandmothers, mothers, and daughters of the shtetl. Perhaps that was why so many of the usual social barriers, between classes and between Jew and gentile, broke down on market day. The women of Eishyshok were more proficient than their men in the languages spoken by the gentile peasants. Many could manage conversations in Polish, Russian, and Byelorussian, and some knew the essential trade words in Lithuanian and Tataric as well. They were familiar with the religion and customs of their clients, took an interest in their families, assisted them with their practical needs, and even knew their tastes well enough to take them into account when ordering stock. Malke Roche’s Schneider, for example, was considered not just a merchant but an adviser and friend to many gentiles. She knew all their woes and sorrows, and would sympathize with them when a pregnant swine was accidentally slaughtered or the crops failed."

Surprising, right? It was to me, anyway. If I'm not alone, then I think it's worth asking, why do so many of us not know about this stuff?

One brilliant explanation has been offered by literary critic Dan Miron. In The Literary Image of the Shtetl, Miron shows how the idea of a Gentile-free shtetl was created by the first generations of Yiddish authors. Focusing on Sholem Aleikhem (whose Tevye stories, of course, are the basis for Fiddler On The Roof), Miron compares the real-life shtetl the author grew up in with his principal fictional one.

Portrait of a Peasant, by Repin

Portrait of a Peasant, by Repin "… there actually existed in Jewish literature ... a potent norm, which demanded the radical Judaization of the image of the eastern European shtetl; it had to be presented as purely Jewish. Only then could it be satirized, exposed as benighted and reactionary, soporific, resistant to initiative and innovation, or, alternatively, portrayed nostalgically and romantically as the quintessence of spirituality and communal intimacy, the nucleus of a besieged civilization that nevertheless enjoyed internal harmony and perfect internal communication. Either rendering demanded an unhistorical Judaization of the shtetl …"

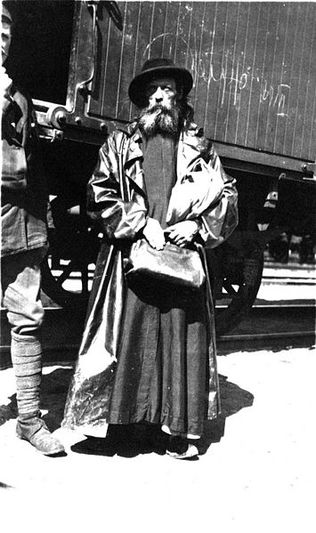

Russian Priest, 1919

Russian Priest, 1919 "… if you think about world Jewry, so many people, if they go back in their family a few generations, they lived in one of these towns … so there is a sense of origin tied to these places that's very powerful … you can go and do genealogical research, and you can read the yizkor book, the memorial book from your family’s particular town and you can find photographs, you can do all kinds of stuff that’s very specific but … they’re fragments, and you need to fill them in. And that exercise of filling in which leaves a lot of open spaces provides great opportunities for people to think into their Jewish past."

Which brings me at last to … priests. My first aim with The Tsimbalist was simply to write a really good mystery novel that took place in a shtetl … but along the way I also wanted to explore some aspects of my own family history. One of our family stories involves a priest, maybe in the very year of 1919 when that character to the left was photographed.

My great-grandmother, Kayla Rubinchik, living in what is now Belarus, had a cow named Masha, who was (as my grandmother said) a very important member of the family. As any cow would, Masha had to be grazed. But Masha was picky about her food. The grass close at hand (or hoof) wasn't good enough for her. And so for a long time, Kayla had to take the cow quite a long away to feed, which required a lot of time and energy from a very busy woman with twelve kids and no husband. This situation persisted until, one day, the local priest took pity on her. He let her graze Masha on his much closer piece of land.

In The Tsimbalist, I wanted to explore the character of an Orthodox priest who would do this kindness for a Jewish family, at a time not long after Tsar Alexander III, pondering the easing of some anti-Jewish regulations, had written: "We must never forget that it was the Jews who crucified our Lord and spilled his precious blood." Was there any tension for this priest, between the personal and the official? Between a specific act and a deeply held belief? Or had the Revolution already happened, and had that changed everything? Or was this priest just a nice guy, and that was all there was to it?

Of course, I have no idea. But it's the kind of thing that makes you remember an obvious but easily-forgotten truth: people are complicated. And also, the kind of thing that makes writing and thinking about this period so rewarding.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed