But last night, I attended a wonderful performance of kobzar music, and at the moment I'd like to talk about that instead. So let me start off by asking ... What's kobzar music anyway?

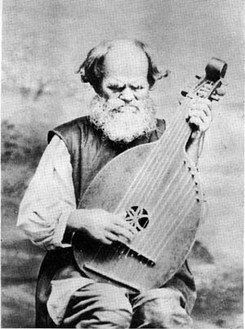

According to the excellent Internet Encyclopedia of the Ukraine, kobzari were "wandering folk bards who performed a large repertoire of epic-historical, religious, and folk songs while playing a kobza or bandura … In the late 18th century the occupation of kobzar became the almost exclusive province of the blind and crippled."

| I'd been wanting to see and hear a bandura for a while because (as if the history of the kobzari weren't interesting enough) I'd come across one or two mentions of the instrument being played in klezmer groups, and wanted to fill in the mental picture sketchily created by that information. So when I saw that Julian Kytasty was performing at Symphony Space in Manhattan, in a concert co-sponsored by the Center for Traditional Music and Dance and the World Music Institute, I eagerly headed on over.* I was very glad I went. Kytasty is a Ukrainian-American singer and bandurist, originally from Detroit, who is recognized as "the instrument's leading North American exponent." (He also composes and plays the flute, among many other accomplishments.) His speaking voice and demeanor are gentle and intelligent, and with his long, gray hair and beard he has a slightly nineteenth-century appearance. | *Sharing the program, by the way, was a wonderful balladeer, Colleen Cleveland. |

When he came on stage, Kytasty told us that, given what is happening in Kiev right now, it was difficult for him to contemplate giving a performance. I don't know whether he was thinking of those events as he played and sang, whether they lent further depth to his singing and playing. But what he gave us was really a kind of soul music.

Kytasty told us that the kobzar's repertoire consisted mainly of allegories, sung, as he put it, "for the 99%", aimed at those in power, and "saying what was really going on, without saying what was really going on." For example (from his last number of the evening, and as best I can recollect):

"Falsehood has taken to calling itself truth. Truth is trampled underfoot, while falsehood is wined and dined. Truth is cast into the dungeons, while falsehood sits in the halls of power. But he who honors truth shall receive great blessing from heaven."

| The kobzari were strongly associated with Ukrainian nationalism. The Internet Encyclopedia of the Ukraine explains that "particularly from the 1870s, the kobzars, including the virtuosos Ostap Veresai and Hnat Honcharenko, were persecuted by the tsarist regime as the propagators of Ukrainophile sentiments and historical memory." And kobzar music was nearly stamped out entirely by the Soviets. This leaves me a little confused as to the question of how banduras ended up in klezmer bands.** Relations between Ukrainians and Jews were not always exactly easy, or friendly (to say the least.) Ukrainians suffered under the thumb of Polish and then Russian rulers; often, they associated the Jews with those ruling classes, and the Jews then suffered for that. Things were not always bad: Natan Meir, in his Kiev: Jewish Metropolis, tells us that "Nationalist Ukrainians hoped ... that the Jews would see themselves as an oppressed nation that might ally with the Ukrainians to throw off the tsarist yoke … the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party (RUP), founded in 1900, condemned the persecution and official repression of Russian Jewry in strong terms … Liberal Jewish organizations in Kiev … collaborated with … Ukrainian organizations to mobilize the electorate in preparation for the Duma elections in 1906 … many peasants voted for M. R. Chervonenkis, one of the Jewish candidates … after the elections two of the non-Jewish deputies–one Ukrainian, the other Polish–pledged to fight for Jewish rights as well as for those of their own nationality." | **Klezmer-related texts include at least two references to bands with banduras in them. Moshe Beregovski, the great Soviet-era ethnomusicologist and klezmer expert, mentions a group consisting of violin, clarinet, cymbalom, bandura, and drum. And the memorial book for the shtetl of Slutsk talks about an ensemble of violin, flute, and bass big bandura. This bass big bandura is possibly the larger, twentieth-century model, with more strings and greater chromatic possibilities, upon which Kytasty also played two numbers. See video below, where Kytasty is joined by klezmer master Michael Alpert. |

| It may be that (coincidentally or not) klezmer bands with banduras in them date from this same period. (Memorial books generally describe shtetlekh as they were in the early twentieth century, and Beregovski was writing in the 1930s and '40s.) | |

"As opposed to ethnic distinctiveness, ethnic closed-mindness is absolutely foreign to folk art. A people always accepts new melodies embodying a familiar spirit, even if those melodies lack the typical qualities of that people’s music. Very often tunes become popular precisely because they offer the new resources of another people’s folk music. It is well known that very similar musical works are found in both Jewish and Ukrainian musical folklore, yet the Jewish tunes are typically Jewish and the Ukrainian typically Ukrainian …"

Besides that, there's this: musicians tend to get along with each other, even when the people around them don't.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed