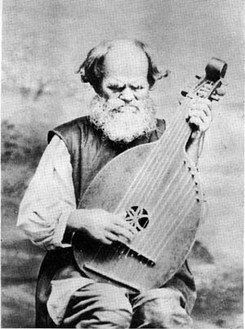

A tsimbalist is somebody who plays the tsimbl.

And what is a tsimbl? A tsimbl is a musical instrument, also known as a hammered dulcimer or cimbalom, which was at one time a basic element of a klezmer band.

One of these days soon I'll be interviewing a real live tsimbalist, who I expect will tell us more about the instrument. Today I want to concentrate on a different tsimbalist, one who played his instrument not in the real world but in the world of literature.

This is a world, it turns out, well-populated by great depictions of klezmer musicians, written by authors both Jewish and non-Jewish. Their depictions have a lot to tell us: about the extraordinary emotional effect klezmer players had on their listeners, about situations in which one might have heard these musicians playing, about klezmer players' lifestyles and the lengths to which they had to go to scrape together a living. Each of these three elements figures in the story "My Tailor Abrahamek," by Leopold Sacher-Masoch. The story also features some wonderful writing (as translated by Michael T. O'Pecko) and introduces us to several of Sacher-Masoch's obsessions: namely, velvet, fur, and female dominance.

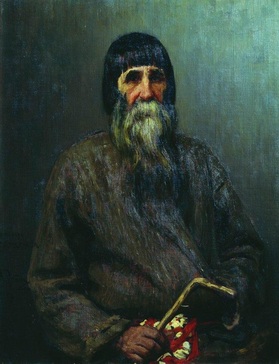

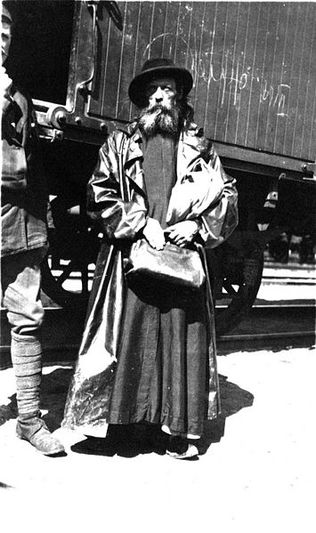

Leopold von Sacher-Masoch

Leopold von Sacher-Masoch Soon after, our Pole goes to a tobacconist's. There, to his surprise, he sees Abrahamek, "sitting in his shirtsleeves, without his caftan, on a low stool by the door ... painting a picture … What was he painting? A Turkish woman with large, dark eyes, in a green turban and a red ermine caftan, sitting cross-legged on a blue cushion and smoking a long Turkish pipe." A sign for the tobacconist.

"Woman was made from Adam's rib,

I tell no lies, that's not a fib.

If just one rib can be so bad,

How much worse must be the lad!"

Next, Abrahamek is seen as a coachman, driving around some noblewomen. "It was truly admirable to see how the little man controlled the rattling coach with his weak hands, driving around a deep pothole or a little abyss here and squeezing between two puddles there; it was like dancing on eggs."

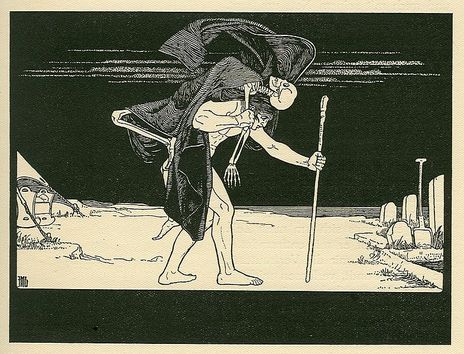

Finally, "I found another Abrahamek just outside town one Sunday, at a tavern where the peasants danced. There was nothing of the painter's quiet earnestness, the wedding jester's joviality, or the coachman's skill about him. Not a single nerve twitched in his stony face, and his little eyelashes were completely immobile, even though his tears flowed unobstructedly, but not down his colorless cheeks. They arose, rich and sorrowful, from the tsimbl sitting in front of him, which he was beating with two small sticks wound in soft, dirty leather, his tone at one moment soft and flattering, as if he were playing with a beloved child, at another wild and forceful, as if he was trying to tame an angry woman by beating her.

"All around him the other instruments screamed, wailed and growled like a zoo at feeding time, and the peasants were stamping around in their big boots, and the girls let their skirts and braids fly around wildly, all this in a cloud of dust that smelled of garlic, brandy, and sheepskins.

"None of that moved him in the least; he seemed to have been transformed into a single big ear with a closed mouth and glowing eyes, listening to the sounds that flowed forth from the moaning tsimbl, which, in turn, was the sound of his own soul. He was an artist at this moment, and God knows what celestial harmonies were revealed to him for the first time in human history."

Leopold von Sacher-Masoch is remembered today mainly as the author of Venus in Furs, and as eponym of the word masochism (although it was not a word he liked.) He was born in 1836 in the Polish province of Galicia, then under Austrian rule. Though a Gentile, he published both a volume of Jewish Tales and a volume of Jewish Tales from Galicia. He was editor, in Germany, of a progressive magazine advocating tolerance and integration for Jews, and also women's suffrage and education.

On the masochism front: according to Wikipedia, "On 9 December 1869, Sacher-Masoch and his mistress Baroness Fanny Pistor signed a contract making him her slave for a period of six months, with the stipulation that the Baroness wear furs as often as possible, especially when she was in a cruel mood."

For example, in "My Tailor Abrahamek," once we catch our breath from that dazzling bit about the tsimbl, the narrator continues: "But while my Abrahamek was painting signs, driving coaches, forging funny rhymes, and playing the tsimbl, my clothes weren’t getting done. I had no other choice but to seek him out."

The narrator arrives at Abrahamek's house, where he meets the tailor's wife, Veigele, whom he finds most attractive: "a full-figured brunette of medium height" wearing "a fiery coat of red velvet that was lined and trimmed with rabbit fur." In the course of conversation with her husband and his client, Veigele gets angry and puts "her hands on her warm, round hips underneath her fur jacket."

After she leaves the room, the tailor explains, "… if you’re going to let yourself be tormented by a woman, she has to be so inclined--and this one is so inclined … Count Starbek always kisses her hands. Why shouldn't he kiss them? After all, it’s as if that little pair of hands were made of velvet, and they're as white as an ermine pelt."

"Abrahamek" is far from the only Sacher-Masoch story featuring velvet, fur and Jewish female dominance--indeed, in others, the element of female dominance is far more prominent. For those who are interested, I'm going to summarize three others of his stories. Why? Because, first, I think it’s nice to pay attention to neglected authors who still have a lot to offer. And second, although I have nothing concrete to say about this, I think it's worth considering how personal predilections and public positions are related in odd ways, how history can be generated by complex personalities in a manner that may not lend itself to neat and clean storylines. I can't think of a better example of this than Sacher-Masoch.

Plus, they're really fun stories:

In one, a pretty Jewish widow known as Madame Leopard (which is also the name of the story) sets out to humiliate the town's worst anti-semite, Agenor Koscieloski, who in spite of his hatred of her race has been courting her. After promising to marry him and be baptized, she carries out her plan: she gets Koscieloski to dress up in the clothes of a Jewish tailor, complete with false beard and peyos, and contrives, while he is in this costume, to have him beaten by a mob of the tailor's creditors. Madame Leopard, wearing a velvet-and-ermine cloak, "her lips wreathed with a smile of cruel satisfaction," "encouraged the crowd from time to time with cries of, 'Don’t spare him! On with your work! No pity, no mercy!'"

In another story, Count Gorewski has been trying to seduce the beautiful Jewess Zobadia. She's actually tempted--her Jewish husband is not too attractive, unlike the count. Nonetheless, in the dark of night, the "pretty Jewess, in her soft furs," and also a red velvet kazabaika, locks the unseeing count into a giant cage intended to hold a vulture. In the morning, "Gorewski stepped awkwardly out of the cage, stretched his stiffened limbs, and left the room without a word; while his charming hostess followed him to the door, stood with her hands on her hips, and laughed aloud till the tears rolled down her face."

In a third story, a different sort of adversary presents himself. In a certain Polish town, the whole community "bent in submission beneath the authority, or rather despotism, of the zadick, surnamed 'the Pious and Just,' whom the Chassidim idolized as their chief … The rabbi … a man of intelligence and irreproachable character, was powerless in the face of this pope of the fanatical Jews, and was forced to content himself with a little body of followers who not alone represented Judaism in its purity and truth, but defended it as well."

The heroine, Volgele, having been singled out as an enemy by the zadick, proceeds to put him in his place. Following an earlier argument about whether women are evil or not, which Volgele has won, the zadick goes out “to hold his discourse under the open sky." Volgele appears in "her blue-velvet cloak trimmed with silver-gray fur" and challenges him to perform a miracle, which he fails to do.

"Come hither," she then says, "that I may crush you with my heel, for you are the seed of the serpent.” The zadick strides toward her, but trips and falls. "With a burst of cruel laughter, and in her eyes a look of triumph that would have fitted an avenging angel, she placed her little foot on her enemy's neck."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed