Spoiler Alert: These are intended for readers who have already finished the book.

CHAPTER 1

Masha the Cow: The bovine who starts all the trouble in The Tsimbalist is based on a real-life cow who answered to the same name. The real Masha belonged to my great-grandmother, Kayla Rubinchik, in what is now Belarus. Masha really did have a habit of getting stuck in the water (a river, in real life.) And the whole village (Jews and non-Jews alike) really would have to come get her out.

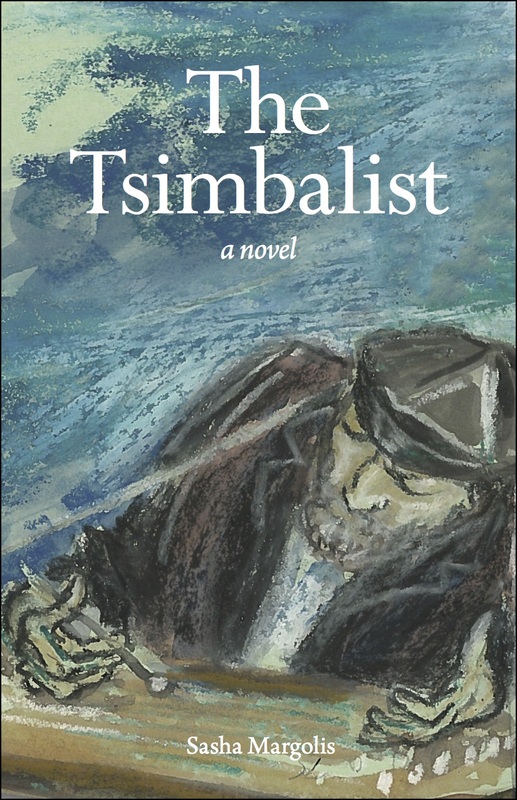

The illustration here is by Dunja Pelto, who also painted the novel's cover art.

Deacon Achilles:

According to my Grandma Rose (Kayla’s daughter), Masha was also a very picky eater. The only pasture the cow found suitable to her tastes was quite a long walk from home, and Kayla spent a great deal of time and energy walking Masha there. One day, however, a local Russian priest told Kayla she could take a shortcut to the pasture through his land. This proved a great time-saver.

Hearing this story, I was always intrigued by what seemed to me to be surprising behavior from a Russian priest toward a Jew. To get a better sense of what Russian priests were like, I turned to an 1872 novel called The Cathedral Clergy, by Leskov (a Russian writer who might have been more famous had he not lived during the same period as Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and Chekhov). The novel (sometimes translated as Cathedral Folk) is about three priests, one of whom is named Deacon Achilles. This Deacon Achilles loves to sing, is tall with a long black braid, and keeps horses. (He also has a servant named Espérance who, in The Tsimbalist, ends up working for Nikifor Kharitonovich instead of the deacon.)

The Deacon Achilles in The Tsimbalist is a composite of Leskov’s Achilles and Grandma Rose’s kindly priest.

The Kelmer Maggid was a real historical person, a major preacher of the Musar ethical reform movement.

CHAPTER 2

Chekhov and Jewish musicians

Bands of Jewish musicians, that is, klezmer bands, appear in two works by Chekhov. I decided to borrow from both, as a way to help ground my work in reality, or at least, literary reality.

In one scene of Chekhov’s 1904 play The Cherry Orchard, a “Jewish Orchestra” plays for a party at the house of a noble Russian family. I took certain lines directly from this scene, including the dancing instructions in French, and the order to a servant to bring tea for the musicians. (“Jewish Orchestra” seems to have been a common term for a band of only a few players.)

The other Chekhov work in which Jewish musicians appear is the wonderful 1894 short story, “Rothschild’s Fiddle,” whose Russian protagonist sometimes plays violin with a band of Jewish musicians led by a certain Moishe Shakhes.

Kuz'ma, the drunken Russian bass player/house painter, is taken (with just a change of instrument) from a memoir written by the famous composer Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908), who writes with typically Russian sarcasm:

“For a long time, the dance band in Tikhvin was composed of a violin, on which a certain Nikolai sawed away at polkas and quadrilles, and a tambourine, virtuosically beaten by Kuz’ma, a house-painter and a confirmed drunk. In later years (ca. 1856) Jews turned up on violin, cymbalom, and drum, supplanting Nikolai and Kuz’ma and becoming fashionable musicians.”

The cymbalom to which Rimsky refers is, of course, the tsimbl.

CHAPTER 3

Beard-burning: Grandma Rose remembered seeing Cossack soldiers burn the beards of Jewish men. There is evidence that this was a widespread phenomenon during the Russian Revolution/Civil War period (when Rose was a girl.) I was not able to find much evidence of beard-burning outside of that time period, but decided to include this incident anyway, set about fifty years earlier.

CHAPTERS 6-7

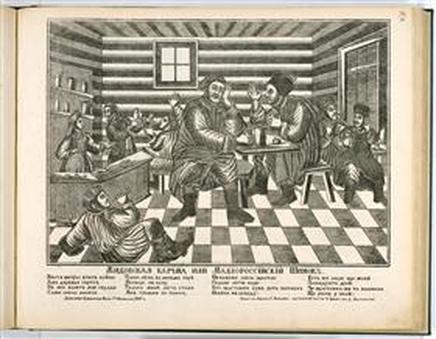

The tavern scene, and the verses found therein, are inspired by this 1868 lithograph of a Jewish tavern, which I found here: http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Tavernkeeping

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, religiously-inspired reformers seeking to wean peasants off of drink tended to blame Jews for the peasants’ endemic alcoholism. And when the pogroms of 1881-82 took place in the Ukraine (these were by far the most serious pogroms of the nineteenth century) the exploitation of the Jewish tavernkeepers was seen by some as one of the causes.

In response, in 1883, the same Leskov who wrote The Cathedral Clergy was commissioned by a group of St. Petersburg Jews to write an essay, “The Jew in Russia: A Few Comments on the Jewish Question.” This essay was intended for the eyes of a government committee established to study the causes of the recent pogroms, and to prevent a repeat occurrence. Leskov’s argument that alcoholism outside the Pale of Settlement was as bad or worse than it was inside the Pale, and that therefore Jewish tavernkeepers were not to blame, is the one I use in Chapter 6.

(Leskov’s attitudes toward Jews were complex. Some of his fiction plays on anti-Jewish stereotypes. But he also wrote sympathetic articles describing Jewish holiday observances, and criticized the forced conscription of Jews into the army.)

One last thing regarding Leskov: the constable in The Tsimbalist who is known as “The Pole” is taken from an identically named policeman in Leskov’s story, “Rebellion among the gentry in the parish of Dobryn.”

A Word About Father Innokenty

In Chapter 6, it is also reported that Father Innokenty has said “We must never forget that the Jews crucified our Lord and shed His precious blood.” In reality, these words were handwritten by Tsar Alexander III in 1890, on a petition to relax Russia’s anti-Jewish policies.

CHAPTER 13

Details of market day in Zavlivoya are taken from descriptions of shtetl markets found in Yizkor books, that is, memorial books, of lost shtetlekh. I paid special attention to books from Czyczew and Krynki.

CHAPTER 18

Dovid: “He saw them murder a bride in her wedding gown ... with a knife ... A bride!”

This alludes to a Yiddish song, “Ver es hot in blat gelezn,” written about the 1871 Odessa pogrom, which includes the stanza:

Dortn ligt a kale a sheyne/Zi ligt ongeton in khupe kleyd,

Lebn ir shteyt a merder eyner/Un halt dem sharfn khalef ongegreyt

(There lies a beautiful bride/She lies there in her wedding gown,

Oh near her stands a murderer/And holds his dagger poised to strike)

Dovid and intellectual trends of the time

The mid- to late nineteenth century was a time of incredible intellectual ferment in Russia, both in a broad political context and in a narrower, specifically Jewish one. I wanted to personify in Dovid several intellectual currents of the time. Two examples follow:

“‘The fact is, Reb Avrom, we Jews have sunk very low in Russia today. We’ve lost our self-respect as a people. Tell me, how long is it that we’ve been perfectly content to be treated as an inferior class, hiding in the study house, cringing before the nobles?’

Avrom didn’t reply.

‘The truth is that instead of demanding to be treated like human beings, we’ve learned to be overjoyed when we’re merely tolerated — and ecstatic when, on occasion, the odd Russian deigns to befriend us. The real tragedy of it isn’t the woe inflicted on us by our enemies. The real tragedy is that that we invite such treatment, with our own inner weakness …’”

Dovid’s sentiments here are a close paraphrase of ideas expressed by the early Zionist Peretz Smolenskin (the “my friend Peretz” to whom Dovid refers) in “Let Us Search Our Ways,” written in 1881, following pogroms in the Ukraine.

Further along, Dovid expresses the hope that “all whom life has trampled, all the worn-out women and starving children, all the alcoholics, the dying villages, and the cities’ horrible poverty and disease – all will disappear into one jubilant chorus of unknown, unprecedented, universal and boundless happiness.”

This is a near-exact quote of Dostoevsky, writing in 1849 in his own defense, while being tried for political crimes. (He was shortly afterward exiled to Siberia.)

CHAPTER 19

Connections to Chekhov and Gogol:

The Efimovski family, in its declining economic situation, bears a resemblance to the Ranevsky family in Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard; while the servant Foka resemble the Ranevskys’ servant, Firs. Foka’s disapproving views on the emancipation of the serfs are the same as Firs’.

Several official characters in The Tsimbalist are inspired by Nikolai Gogol’s 1836 play The Inspector General. Anton Antonovich Skorokhodov-Druganin, Zavlivoya’s petty-governor, shares the close-cropped grey hair, riding boots, and corrupt character of Gogol’s Anton Antonovich Skvoznik-Dmukhanovsky, who is either mayor or governor depending on the translation. (I opted for petty-governor as a compromise.) Police sergeants in Gogol’s play are named Pugovitsin and Svistunov, while the police captain is named Ukhovyortov. The Gogol play centers around a traveler at a tavern who is mistaken for a government official, in the same way that The Tsimbalist’s Pugovitsin is taken to be an agent of the Third Section.

CHAPTER 20

The artist-and-millionaire colony of Boyarka, near Kiev (the town where Nikifor Kharitonovich apprehends the three thieves) was Sholem Aleikhem’s model for the town of Boiberik. In Aleikhem’s Tevye stories, Boiberik is an important locale: early on, Tevye, still a wood delivery man, rescues two lost Jewish women from the forest, and delivers them to the dacha where they have been staying. As a reward, he receives money and a cow, which allow him to become a dairyman. In The Tsimbalist, the amusing Jew who has just delivered wood to Boyarka when Nikifor Kharitonovich meets him is meant to be Tevye.

Finally, a fairly complete bibliography of books and articles I consulted, for those interested in further investigation:

Antonov, Law and the Culture of Debt in Moscow on the Eve of the Great Reforms, 1850-1870

Baumgarten, Yiddish oral traditions of the batkhonim and multilingualism in Hasidic communities

Becker, Judicial Reform and the Role of Medical Expertise in Late Imperial Russian Courts

Beregovski-Slobin, Old Jewish Folk Music

Boyarin, Unheroic Conduct

Davis, Jews and Booze

Deutsch, The Jewish Dark Continent

Eliach, There Once Was A World

Etkes, Rabbi Israel Salanter and the Mussar Movement: Seeking the Torah of Truth

Frank, Crime, Cultural Conflict, and Justice in Rural Russia 1856-1914

Glaser, Jews and Ukrainians in Russia's Literary Borderlands

Hearne, "‘Dangerous Women’ – Prostitution in Late Imperial and Post-Revolutionary Russia"

Herlihy, The Alcoholic Empire

Horowitz, "Tsimbls and Their Kin"

Hubka, Resplendent Synagogue: Architecture and Worship in an Eighteenth-century Polish Community

Kesi, Russian Vodka, A National Tragedy

Livak, The Jewish Persona in the European Imagination: A Case of Russian Literature

Lovell, Summerfolk: A History of the Dacha

Masor, The Evolution of the Literary Neo-Hasid

Matisoff, Blessings, Curses, Hopes and Fears

McReynolds, Criminology, Forensics and Identity in Late Imperial Russia

Miron, The Literary Image of the Shtetl

Opalski and Bartal, Poles and Jews: A Failed Brotherhood

Pipes, Daily Life in Imperial Russia

Pokhlebkin, A History of Vodka

Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia

Potichnyj and Aster, Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective

Presner, Muscular Judaism

Roskies, The Shtetl Book and A Bridge of Longing

Rosslyn, Women and Gender in 18th-century Russia

Rubens, Jewish Costume

Schauss, The Lifetime of a Jew Throughout the Ages of Jewish History

Strom, The Book of Klezmer

Zborowski and Herzog, Life Is With People

Yizkor Books read online at jewishgen.org

YIVOencyclopedia.org, many articles

Akunin, Erast Fandorin series

Aleikhem, Tevye the Dairyman; Stempenyu

Babel, “Shabbos-nokhomu”

Chekhov, “Rothschild’s Fiddle”; The Cherry Orchard; “Mire”; “The Steppe”; “At the Barber’s”

Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, tavern scene

Gogol, The Inspector General, “The Nose”

Leskov, Cathedral Folk and “Rebellion among the gentry in the parish of Dobryn”

Mickiewicz, Pan Tadeusz

Sacher-masoch, Jewish Tales

Shchedrin-Saltykov, The History of a Town

Tolstoy, Childhood, Boyhood, Youth; Anna Karenina

Turgenev, Father and Sons

RSS Feed

RSS Feed