I doubt whether this timely reminder stopped many Jews who saw it from participating in various Valentine’s Day rituals. Those forces of convention and commercialism are awfully hard to resist.

But his video did make me think: Hey, maybe I should take this opportunity to talk a little bit about love and courtship back in shtetl days--and specifically to ask, was there any love involved in courtship? That is, exactly how antithetical is Valentine’s Day to Eastern European Jewish tradition?

As usual, the test case for shtetl image vs. shtetl reality is Fiddler On The Roof. That's particularly so in this instance: the question of how young people manage to pass from single to married, and what that means for society, is a running theme in Fiddler ... just as it is in Sholem Aleikhem's Tevye stories, the basis for the musical … and just as it is in the works of Jane Austen ... which I only mention because some people have actually put about the delightful theory that Aleikhem based his stories on Austen's novels, or have at least noted the similarities between the two.

Somebody even did this:

Jane Austen aside … and to make a long musical short: In Fiddler On The Roof, the power of "tradition" keeps getting weaker as the power of new-fangled, Western-style love (Valentine's-Day-style love) grows stronger. If tradition finally makes a stand in refusing to accommodate intermarriage ... still, you have to say that, overall, the West has won.

So: Is the picture of tradition that Fiddler paints accurate?

Here's what Hayyim Schauss says, in The Lifetime Of A Jew: "Falling in love was considered an extraordinary and abnormal phenomenon, a sort of mental disease occurring once in a great while among the very wealthy or the very poor, the only groups who dared to flout the conventions of social decency."

Well, well, well. Score one for Fiddler On The Roof: Marriage really didn't have much to do with love.

Rather, it was in part a business arrangement, and in part a way of perpetuating a culture that prized, above all else, learning. The most sought-after grooms were scholars. The better the scholar, the bigger the dowry. Not only that: dowry arrangements included provisions for the support of the newlyweds, room, board, and more, sometimes for years, in order to enable the scholarly young bridegroom to continue to do nothing but study (and perhaps also make little scholars.)

Do you remember the ethnographic survey I mentioned last time, the one carried out from 1912-1914 by S. Ansky? If you're in any doubt about the massive importance of the dowry in Eastern European Jewish life, check out these questions the survey asks:

"Do feuds often break out on account of dowries?"

"Do you know of any cases in which the groom did not go through with the marriage until the entire dowry was delivered to him?"

"What living expenses are generally included in this?" "Are clothes included?"

"What kind of guarantee do people give for this? Is a Jewish contract enough, or do people require a legal promissory note or notarized document?"

Something else that left little chance for romance: in many cases, bride and groom came from different towns, and were barely acquainted before the wedding. This is where matchmakers came into the picture.

But here, those points we awarded to Fiddler On The Roof are going have to come off the board. If I'm not mistaken, in most people’s minds the archetypal matchmaker is Yente (as played by Molly Picon, who was last seen pretending to be both a man and a violinist in Yidl Mitn Fidl.)

But the truth is, most matchmakers were men. What sort of men? According to Hayyim Schauss: "Matchmaking required a special aptitude. A professional shadchon had to have an air of importance and dignity in order to arouse confidence. He usually wore good clothes and carried a cane. He led up to the subject very cautiously and made every proposal in a tortuous and indirect manner. He was skilled in hiding and distorting facts, especially when the bride and groom were from two different localities."

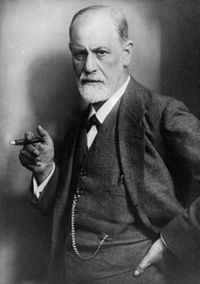

This skill was made fun of in one of Sigmund Freud’s favorite Jewish jokes: "The young man was most disagreeably surprised when the proposed bride was introduced to him, and drew aside the shadkhen—the marriage broker—to whisper his objections: 'Why have you brought me here?' he asked reproachfully. 'She's ugly and old, she squints, and has bad teeth …' 'You needn't lower your voice,' interrupted the broker, 'she's deaf as well.' (Quoted in Ruth Wisse's No Joke)

There was one respect in which shtetl romances did resemble today’s. After the engagement, bride and groom sent each other love notes. As Schauss relates, "They also wrote letters to one another. These letters were distinctive in character, consisting of high-sounding, stereotyped phrases. In most cases, the betrothed couple did not write their own letters, but delegated the task to a man in the town who had a beautiful handwriting and the ability to use pompous language. He used the same phraseology and the identical expressions in most of the letters which he wrote ..."

The Cyranos of the shtetl … or maybe just the Hallmarks.

Update: I meant to include a fun tidbit illustrating the very false impressions these letter-writers could sometimes create, just the way that Cyrano did.

A story by nineteenth-century writer A. S. Friedberg includes two such characters "who penned letters in very elegant German in the names of a bride and a groom. Each betrothed was convinced that the other was fluent in German, while the truth was that both the groom and bride-to-be were entirely ignorant of that language."

(Described by David Assaf in Journey to a Nineteenth-Century Shtetl: The Memoirs of Yehezkel Kotik.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed